I’ve been traveling today, so I didn’t have time to write earlier. This morning, before I left, I was having my eggs and toast and orange juice while looking out over the beautiful Ozark Plateau and what do I behold but Aaron Renn’s latest in Compact: “The Cultural Contradictions of Conservatives.” I was not impressed, but I had to get on the road, so I had most of the day to contemplate why I disliked this article, and then I got home and reread it a couple times and discovered that I agree with more of it than I initially thought.

So, good lesson here: always read three times before flying off the handle.

But also, I’ve been thinking about this little essay all day and I’d like to get a little writing in before bed, so we’re doing it anyway. Just with a less vitriolic tone.

Who Wants to RETVRN

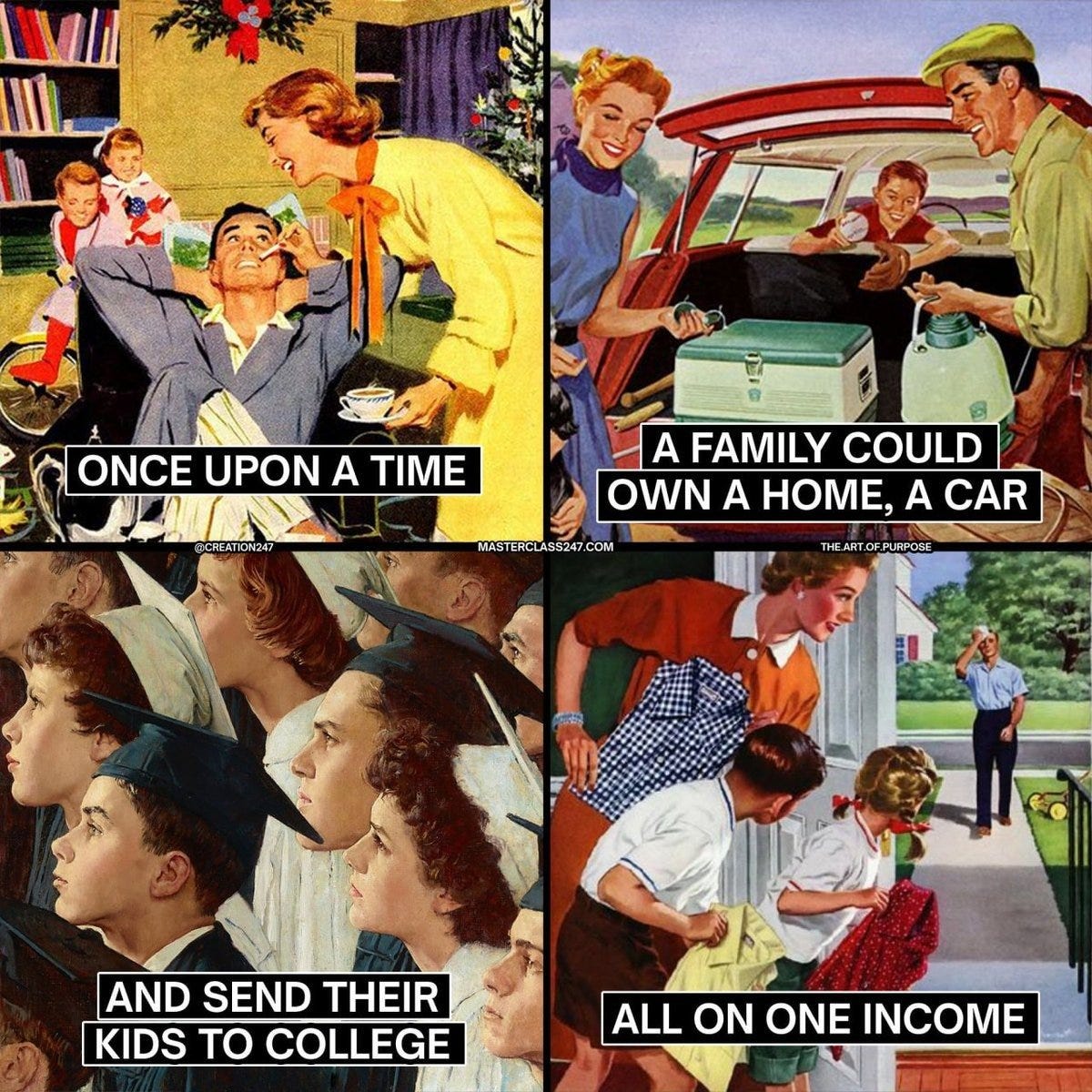

Renn’s argument is that there is a kind of online conservative who uses memes like the one posted here to argue for a particular type of traditional lifestyle, but that the people actually living that lifestyle are largely liberals. The headline is doing is his essay no favors, though, because as the argument develops he is making a much narrower point that the very online conservatives, importantly, people that the Trump Administration is paying attention to, are describing ways of life that most Republicans don’t want. He thinks this explains part of the disconnect between the conservative elite and popular factions as the elite are listening to voices that are, at minimum, highly idiosyncratic about their desires.

And for the most part I’m in agreement with the general thrust of the thesis. The conservative elite’s love of New York City, Southern California, and New England is at odds with the conservative voters who tend suburban or rural, Southern or Midwestern, and while many of them have college degrees they typically top out at the BA level and have no great affection or deference to people with lots of letters after their name.1 This is hardly the only such division, and I believe Renn has highlighted others in the past. The Conservative elite is High Church, the voters are Low Church (largely Baptists and other Evangelical denominations). The Conservative elite is functionally libertarian, even if they sometimes make noises about socially conservative domestic policy; but the voters are not libertarian. They aren’t socially conservative either, which goes a long way towards explaining Trump, but the key point is that there are numerous elite-popular splits in the GOP and the Conservative Movement.

But when it comes to describing this particular divide, the evidence provided is woefully insufficient.

He writes:

Ask yourself: Who is more likely to be buying traditionally produced artisanal products? Who is more likely to prioritize “buying local” over patronizing the big box chain? Who is more likely to preserve or rehab historic buildings? Who wants to landscape with “native plantings”? Who actually lives in those cute New England towns? To ask these questions is to answer them.

Which is a very nice rhetorical trick, but I’m an obstinate reader so I’m going to reply that, in fact, I don’t know the answer to any of those questions except for the last one (New Englanders). We’re supposed to obviously say that it’s liberals who buy local and preserve or rehab historic buildings or landscape with native plants. Except I live in a county that went 63% for Donald Trump in 2024 and I have many friends who do stuff like that. I haven’t inquired of their politics, but I know all of them from Baptist church that meets in a high school and our kids are friends and many of them are involved in agricultural and manufacturing fields, they like to shoot and fish, and they could totally be Kamala voters, but I’m just saying I’m not betting that way.

The local Walmart advertises produce from local farms -we’ve had a glut of strawberries for the past month as every farm in the region is selling off their harvests. We’re starting to get corn now. Every farm in the region sells some of their produce either at the farmers market or at the farm itself. I can even buy up to an entire slaughtered cow if I have a way to get all the meat back to my apartment (and if I had a much larger freezer).

The women I know at church love landscaping with local flora, and they often know a great deal about it because they are from this area or areas even further east in the Mountains. Some of them even transplant from their own family’s gardens and houses.

I will admit that the person I know who rehabs historic houses and has turned a couple into Bed and Breakfasts is my bet for the massive liberal in my friend circle, but she is also very much in my friend circle and I’ve seen all the very rural and conservative and persnickety men who like to shoot guns and complain about commies listen attentively to her describing how she refurbished a couch that Abraham Lincoln might have once sat on.2

Now, which is the more common among Conservative voters? I don’t know. But the point is, I’m not aware of any data on this point, so right now we’re just vibing.

Theory in Search of Data

Renn also highlights the city of Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania; which was recently profiled by the Financial Times for being a blue city in a red part of the state. Here’s their glamour pic:

Stroudsburg if a little shy of 6000 people, nestled in the Poconos and though Reddit tells me it is “not really culturally part of Appalachia” it’s listed as a distressed county on the Appalachian Regional Commission’s map. And according to the Financial Times it’s apparently a “well-governed, high functioning town” which is not the expression I would use to describe a city with an 11% poverty rate, but again, it’s late so I’ll let it go.

Renn asks what the equivalent Republican city is. Easy. Mount Sterling, Kentucky -which I pick because I’ve been there and not because I’ve done an exhaustive search of every Appalachian small town from Mississippi to New York. Glamour shot:

And actually, that’s a terrible shot because it’s of the Main Street facades (which, note, are well maintained) but you can’t see the Courthouse Square where the real business is. Here’s a picture of that from Mt. Stirling’s Tourism Bureau:

Now, of course, the question is how does Mt. Sterling vote. And the answer is that Precinct 1 of Montgomery County, KY voted 69% for Donald Trump. Mt. Sterling is a little larger than Stroudsburg, it’s a good bit poorer, and a couple years younger. But I’ve been there, I’ve met several of their elected officials (who may well be Democrats, but Kentucky local elections are non-partisan) and they seem generally competent.3

But really, these aren’t great comparisons because both Stroudsburg and Mt. Sterling are mountain towns in Appalachia which have always been politically weird. Right next door to Mt. Sterling is Menifee County, which only started voting Republican in 2012. Montgomery only started in 2000.

And that’s my real complaint: local communities in America are highly, highly diverse. Glancing at a couple Financial Times essays or clicking around on the New York Times precinct map is not data. There are 89,000 local governments in America and they are all special in their own unique ways. We have so many precisely because Americans are weirdos who like to create communities that are weird.

So, yes, I will agree that the Online Right’s fascination with Norman Rockwell probably doesn’t describe most Republican voters, but that’s because Republican Voters are still Americans and their local preferences are all wildly divergent.

Some Notes for Theory Building

Again, I’m largely in agreement with Renn’s argument that the elite and the common factions of the GOP and Conservatism are often dissimilar and that the elite does a poor job of keeping track of what Conservative voters are really like. But I think we need a somewhat more systematic assessment of what Conservative voters really want. Doing so is hard, though, because the Conservative coalition is not now, and has not been for a while, held together by a positive vision of anything. As I’ve written before, the Republican Party has a very hard time organizing for political advancement and instead is held together largely by opposition to Democrats using public money to fund Democrat interests. It’s not surprising, then, that the GOP local communities would range from mountain towns to farming towns to suburbs to rural to rivers to villages and pretty much anything except the major cities, places with universities, and apparently Vermont (which, though not technically in Appalachia, I suspect has the same “only enough political resources to support a single political machine” background).

Such a survey would be a breathtaking adventure. But I have a couple ideas for potentially narrowing the scope of the questions, if not the necessary geographic breadth.

How rooted are the communities? Mt. Sterling’s city government is filled with people who have lived there since they graduated high school in the 1980s. They traveled in various ways, but they all came home. That indicates a level of rootedness and family connection that goes back a long way and also produces the kinds of cultural events that brought the city to my attention.4

How much are we talking about gentrification? What happened in Vermont is a fascinating question and I hope some day someone provides a comprehensive answer. However, just looking at their economic and demographic data, it looks like the state hit hard economic times in the inter-war years, and hadn’t even been growing that much in the late 19th century. It didn’t get a lot of growth in the post-War boom, either. The population explosion starts in the 1970s (I mean, relative to the existing baseline, the state’s still not populous) and state politics doesn’t switch until the 1990s. Which reads “gentrification” to me.

Something I’ve learned in many years working around and adjacent to city planning and historic preservation is that historic architecture is the legacy of bad economic times. In a healthy economy buildings are modified to fit current tastes or to expand their usefulness. Sometimes a historic building will be, at great expense, converted back to a past configuration but that’s fairly rare. If the economy is healthy, nothing stays put long enough to become historic or classic or interesting. Cities “need” 30 years of bad economic times for the buildings to cycle through from “needs a new coat of paint” to “obsolete” and then back around to “historic!” But the city then needs something to happen to make the land valuable enough for the historic properties to be refurbished as historic properties.

Read an article many years ago, alas I couldn’t find it now if I had to, about why historic preservation and gentrification aren’t taking off in Detroit. The gist of the argument went as follows: while the destruction of Detroit’s economy has lasted long enough to leave many historically interesting structures, the continuing awfulness of Detroit’s economy means that anyone who actually bought and refurbished a building would lose money. The cost of materials to rehab an historic building would be more than what the finished building would sell for because the new owners would still have to live in Detroit. But, if there is something worth living in a location for, the dilapidated buildings would be a cheap way to move into the region. The buildings would then be refurbished over time and we’d get the Vermont villages we see today.

Wikipedia’s description of Vermont’s shift largely follows what I’d have guessed. The population shift in Vermont was driven by New Englanders and New Yorkers looking for nearby cheap housing, and Vermont’s multi-decade economic malaise made them a prime target. Which is a long way of saying the people who live in Vermont and make it look like a village Conservatives would like to live in are not the people who built those villages. All the original inhabitants were displaced or died. In other words, it’s not deeply rooted conservative community. It’s a skin suit. And as Vermont’s economy starts to falter, people are moving away from it.

Conservatives don’t agree on the aesthetic they are trying to conserve, but maybe it isn’t the aesthetic that matters? I don’t actually know any conservative who unironically says RETVRN or aspires to a Norman Rockwell world. But I know lots of people who wish their houses had actual dining rooms.

And while I don’t know anyone who wishes for the kitschey aesthetic, I know several women who wish they didn’t have to work to make ends meet, wish they thought they could afford more children, or worry about how they are going to send their kids to college and would really like more stability and flexibility in their life, rather than constantly flopping from one economic and political crisis to another.

They are probably perfectly happy living in modern suburbs or small towns, like their cars, and don’t mind getting their locally sourced corn on the cob from Wal-Mart. But Republican politicians could probably make some progress on keeping housing prices down so they didn’t have to choose the cheaper open floor plan with a kitchen dining hutch when they bought their house.

If We’re Gonna Vibe, Let’s Vibe.

All of this to say, I think there are productive ways to discuss the vibes of Conservative community, and I think there are some important empirical questions we should probably try to answer in the near future. But we we need to actually think through what the vibes are and actually gather the data to answer these questions and not overthink an overly-online meme.

As someone with lots of letters after my name, I think the conservative voter’s lack of reverence is entirely justified.

Fine, I was attentive. They might have been polite, but their wives were also paying attention. And the men were definitely interested in her views of sheep herding and horse raising, because many of them keep sheep and horses, too.

Who knows, maybe these are the only flaming libs in Mt. Stirling. Judicial elections are partisan, and the two judges are Democrats, but again -this is the Mountains and politics is just weird out there.

Though it is also hardly the only such city. I continue to be in awe of the city of Corbin turning it’s name around to host the Nibroc Festival and the dang thing worked.

The Rust Belt kind of breaks your "Something I’ve learned in many years working around and adjacent to city planning and historic preservation is that historic architecture is the legacy of bad economic times." point.

My city of South Bend - and dozens others like it - experienced some of the worse economic forces that the U.S. faced in the last 60 years. Certainly some of them did a better job than others of preserving the great historic per WW2 buildings and built form, but the vast majority used the narrative of the local economic decline to demolish their downtowns during urban renewal.

Also one thing that gets conflated with this issue is the centuries long culture war between the Puritans/Yankees and the Scots-Irish/Borderers/Appalachians, as described in "Albion's Seed". (If you haven't read it, you should.)

New England towns were built by Puritans with all the hoses close together so that all the neighbors could keep track of each other and make sure each of them was living in a suitable pious and God-fearing manner.

Meanwhile the Appalachians built their houses far apart because it's not of the neighbors' business what a man does on his own property.