Life in Prison

A Look At America's Prisons and Jails

I’ve been bouncing around the edges of corrections and prison policy since I was a kid. Several of my pastors growing up were chaplains at the local prisons. My brother, a pastor, lives in a city with a state correctional facility and he is there at least monthly. This was just the background of my life. Matthew 25:43, “(I was)…in prison and you did not visit me.” In High School I found Charles Colson’s book for Prison Fellowship Ministries, and saw Steve Geyer preach/perform at a retreat and he related stories of his own time in prison ministry. By the time I was in college I was actively researching prison reform and even lightly lobbied for the Prison Rape Elimination Act.1

Professionally, I don’t get to do as much with it as I’d like. I ultimately did not become a criminologist. But I study local government, so even if I don’t get to go into prisons very often, I am frequently talking about them at some level, and I try to keep abreast on the area.

Prisons are complex institutions, and corrections policy isn’t a very popular area. On the left, the loudest voices think corrections are immoral, that crime isn’t a big deal, and all crime is really just the working out of societal iniquity anyway, so you deserve it. On the right, the loudest voices think corrections is easy, you just lock people up and throw away the key. On the ground level, working with police, prosecutors, lawyers, judges, and the myriad social services that surround public safety, the reality is a good bit more nuanced.

I start with this prologue because I want to be clear that I have policy desires for our prisons. I read and analyze the data we have to achieve certain goals. And since most of the data produced in corrections policy is also produced for a purpose, it is important for people learning about corrections to know that the data, even the good data, was produced by people with a point. A key ability in policy analysis is to recognize the framing, but still be able to independently interpret the data. My goal here is not to convince my readers of my policy preferences -that’s for another day -my goal is to show why corrections policy is complex and also why we try to do it.

So. Let’s dive in.

How To Reduce Crime

The first major nuance about public safety is that crime and corrections are different policies. Crime policy is about preventing crime, or -having failed to do that -catching the criminal. Corrections policy is about what we do with the criminal after they have been caught and convicted.

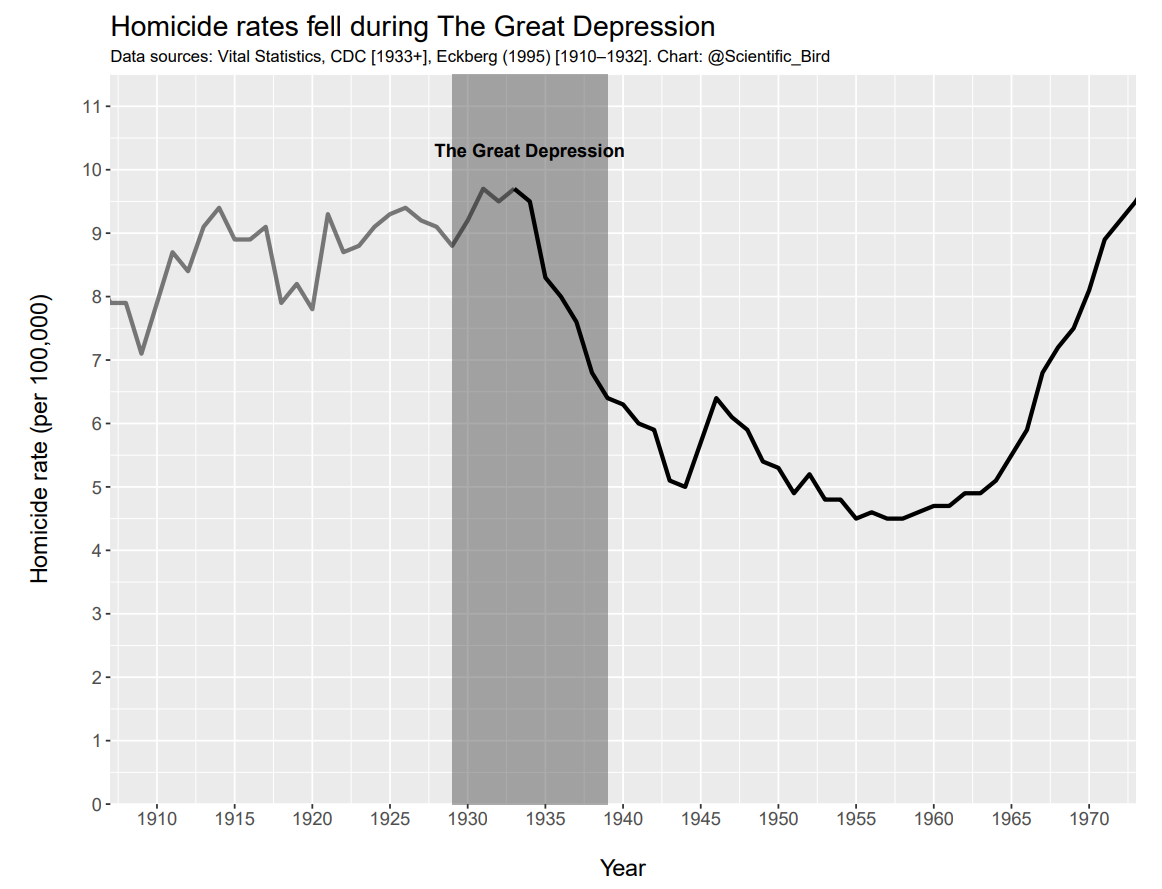

We don’t know what causes crime. The usual stories don’t hold water. People will argue that it’s caused by poverty, but at a macro scale crime and economic conditions don’t correlate very well. And at the micro level most poor people aren’t criminals, and most criminals have family members who aren’t criminals.2

In the same way, while intelligence does have some effect on criminal behavior, and criminals are quite dumb, the causal story doesn’t quite work. The estimates of prisoner IQ I keep finding are all in the general vicinity of 90, and have been since the 1930s. An IQ of 90 is below average, but still well inside the normal range. Low IQ predicts violent reactions from convicts, but most people with low IQs aren’t violent.

Additionally, fully 10% of Americans, simply by virtue of the way IQ is measured and scaled, fall into the “Borderline Intellectual Functioning” category of people who are too functional to be institutionalized, but not functional enough to manage life in the world we’ve created. But we only incarcerate about 1% of Americans.

What we do know about crime is that, whatever its cause, it is attracted to chaos. Disorder is the handmaid of crime, and if we want to reduce crime then reducing chaos is the most effective way to do it. And this isn’t a new insight. People have been publishing these papers for 3 decades or more. It was the base insight of Broken Windows Policing. Not “zero tolerance,” not “people who break small rules also break big ones,” but the insight that criminals, whatever their intellectual abilities, have enough sense most of the time to not commit crimes in front of police officers or in places that are orderly enough that the criminal activity will be immediately spotted. Criminals generally want to get away with their crimes.

Most of the time.

So we reduce crime by increasing the likelihood that a criminal committing a crime will be caught so they simply move on. Enough jurisdictions in a metropolis put enough police on the ground to patrol the entire area with impunity and you can drive the crime rate down to zero.3 Crime today collects in places where police have a hard time going.4

In short, if your only interest is lowering crime, implement stage 1 of Charles Fain Lehman’s Criminal Justice Agenda and call it a day.

What About After?

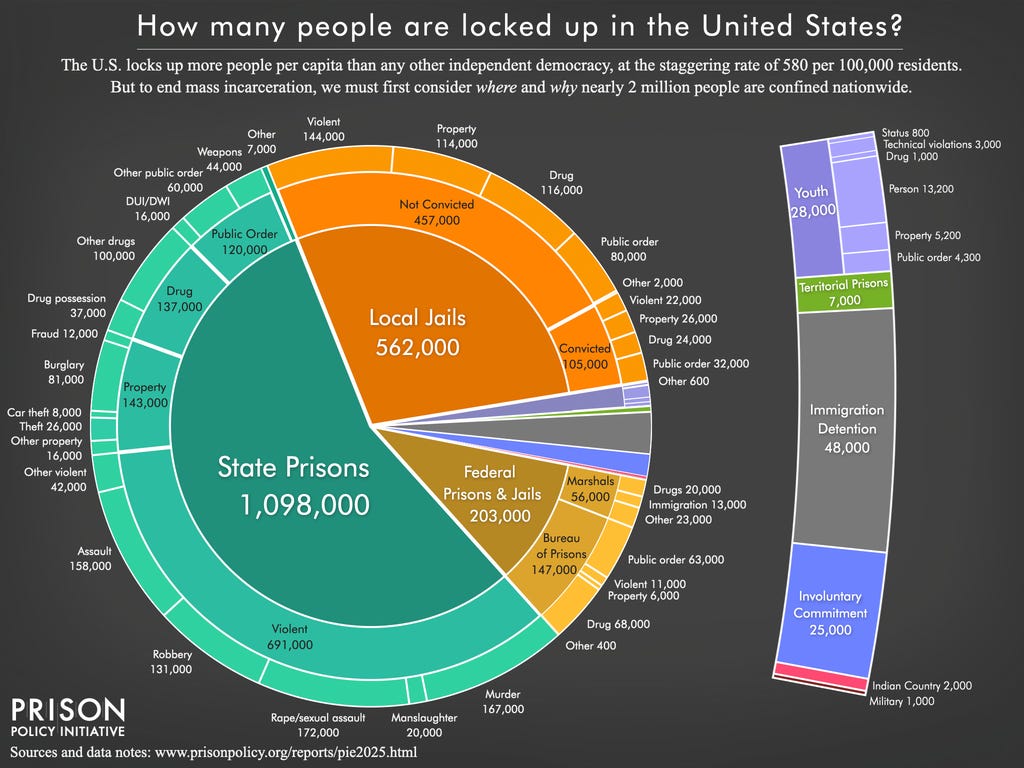

The question that has long bothered me, though, is what do we do with the person after we’ve caught them, tried them, and convicted them?5 Normally on this point I’m arguing with very empathetic left-leaning people who think prison is so cruel and crime so insignificant -really, it’s just drugs! -that we should abolish prisons. And I’d like to draw your attention to the above pie chart of the American Prison Population to kill that idea. Over half the people in state prisons are there for statutory violent crimes.6 And people, including Prison Policy Initiative from whom I got the chart, like to point out that the Federal Government arrests a lot of people for drug crimes, and that’s true. But the DEA doesn’t leave the office for personal use amounts. That’s local police’s problem.

The Four Rs

Once a person falls into the hands of the corrections system, there are historically 4 approaches Americans have taken, which conveniently can all start with the letter R.

Retribution: The most basic approach is the Justice approach. A person has harmed society, and so to balance the scales of justice we harm that person back. Corporal punishments, fines, imprisonment -all of these can by defended by reference to the just retribution for crimes committed. This can sometimes sound harsh, but CS Lewis points out that it is actually the most limited response a society can take. Retribution must be proportionate to the crime if it is to avoid becoming a crime itself, and so retribution imposes a limit on what we can do to people. Even Don Vito Corleone gets this when Amerigo Bonasera asks for his daughter’s attackers to be killed. “That is not justice, your daughter is still alive.”

Restitution: Second, the person who has harmed can restore what has been destroyed. A thief can return what they have stolen. A murderer can pay the wergild. A vandal can clean up what they’ve defaced. The upside of restitution is that, in an ideal world, it ends the matter. No blood feuds. No lasting harms. It can even restore relationships between people because restitution can include an apology that can lead to forgiveness and restoration. The problem with restitution is that some things cannot be replaced, and even when we impose fines and penalties the victims and society may not be satisfied with the justice of the punishment.

Restraint: Third, we can imprison a person as a threat to the society at large. This is a protective measure -by committing a crime they have demonstrated that they cannot be allowed freedom within the society, and so they are denied freedom within the society. Restraint can include exile from the community,7 but it’s usually a prison sentence. A lot of libertarians like this because it seems to go well with the non-aggression principle -we’re restraining the person’s liberty until they are no longer aggressing us -but I confess to finding this one among the most civil liberty threatening approaches to crime. It’s the logic that would justify locking up every man under the age of 35 until he was old enough to be statistically unlikely to commit a crime.

Rehabilitation: Finally, we can try to treat the prisoner in such a way that, when released, they will be unlikely to re-offend. Ideally, this would lower the crime rate, but as noted above we’ve had really bad luck with it. Lowering crime is about policing, not corrections. And, like restraint, unbound from desert this is the other great threat to liberty and safety. Medicalization of corrections runs both intolerable risks -that a sadistic doctor would torment the prisoners forever and never declare them rehabilitated, or that an overly empathetic doctor would declare monsters safe for society and release them.

It has long been my contention that, for a free society, Retribution can be the only justifiable response to the conviction of a crime, and I’ll get a bit into the reason why in a moment. However, I see no conflict in choosing as our means of retribution techniques that have restitution, restraint, and rehabilitation as their side effects so long as they constrained to just desert.

Who is in Prison?

To sum up to this point, I don’t care about recidivism. It is the police’s job to make sure crime doesn’t happen, and the primary purpose of corrections is punishment. Anything else that can be gained from the punishment is merely extra. What I care about is whether the punishments are just.8

But I’m not God and I’m not a judge and I’m not the state, so my views aren’t definitive on the matter. And in the system in which we live many people are less interested in the justice of the sentences than they are in rehabilitation (usually to my left) or restraint (those to my right). And as each of these views is held by a large enough group of people to demand a policy response, the result is a corrections system that largely fails at all four because it is designed to do all four for everyone, regardless of the circumstances of the criminal and the crime.

To learn about this, I’ve spoken many times with the police, judges, the jailor, the warden at the neighboring prison, the prosecutors and public defenders, and something I highly recommend to you: gone to watch the trials at the courthouse. At least here, Tuesday and Thursday are trial day.9 They tell me that the people they arrest, try, and convict fall into roughly 4 categories.10

Drunk, High, Stupid, or Wanting to Be: The largest category is someone who has a substance abuse problem. Statistically, 65% of prisoners surveyed had used an illicit substance in the past 30 days before their arrest. Half of prisoners have a substance abuse problem. According to the prosecutors, when you add alcohol to the list, it’s 80% or more of their cases. Drugs and alcohol reduce your judgment and your inhibitions -they make you stupid -and stupid people, as the wonderful criminologists pointed out earlier, respond to situations with violence.

People who want drugs commit property crimes to get goods they can pawn to pay for drugs. And these people are frequently getting arrested because -being drug addicts -they keep getting drunk, high, and stupid and committing crimes. But by the police’s own assessments, these aren’t useless people. They’re people with a serious problem that we at present have no way to resolve except using prison.

And they’re probably most of the people in prison. Even some of the murders and manslaughters are people suffering for one incredibly stupid decision. We’ll come back to this later.

Low Level Organized Crime Functionaries: The next category, which has a great deal overlap with the previous category, is people who are involved in organized criminal enterprises but are not part of a criminal gang. This is important, because members of criminal gangs often have criminal records that would prevent them doing things like buying a gun or renting an apartment. So they use people who have clean records to do those things for them. The apartment is in the name of an unrelated person. Their sister buys the gun. The car is rented in the name of the driver who doesn’t know what they are carrying (though should really be able to guess). These are also the people doing the actual theft for shoplifting rings. Most of these people are also drug users because they get into doing this stuff because they have debts from their drug use.

Cops would love to flip these people and get them to testify against actual organized crime members, but for the most part these criminals won’t testify. First, their crimes are usually fairly minor and the punishments the prosecutors can threaten them with are not very scary to them, especially if their patrons offer to protect them (or compared to the threats their patrons can make).11 This also, incidentally, covers a lot human trafficking cases. So we send these people to prison, and when they get out they are fairly unlikely to reoffend. Having a criminal record, they are now useless to the organized criminals they were working with.

Actual Hardened Criminals: It is fairly rare, but there are sometimes people who are just hardened criminals, but not insane.12 Whether they are rare in the world, or just rare in the courtroom because they have the ability to evade detection is a question I can’t answer. Some of these people are are members of organized crime groups. One of the men we convicted of murder a couple years back the coroner is convinced killed several more people as part of a gang before he was caught, but couldn’t prove it. In any case, the man was completely unrepentant and unnerving to the police and prosecutors.

These are the people that push the hardest against my dislike of pure restraint policy because while they may be impulsive, they are not stupid. They are intensely rational criminals and they will commit more crimes once released if they think they can get away with it.

High Level Organized Crime: This is the golden ring. The police would love to get these people, but it is almost impossible to do so. They have money and enough intelligence to distance themselves from overt criminal activity. These are the people the police would love to get their low level flunkies to flip on. But, alas, most of them are out of police reach. Heck, most of them don’t even live in the jurisdiction where their crimes take place. This is another category we’d really like to keep in prison.

What Do We Do With the Drunken Reprobate?

The problem facing police and prosecutors is that most of the people who we put in jail are not criminal masterminds. They’re the first category: drunk, high, and stupid. But most people who are drunk and stupid, and probably most people who are high, aren’t criminals. So the question is why these drunk, high, and stupid people are criminals. And are there better options for them?

And an entirely reasonable solution is to just keep putting them in jail. It’s an expensive solution, but it is not an unreasonable one. Another solution, as noted above, is to increase police pressure so they have fewer opportunities to commit crimes. But if we could rehabilitate these people, it seems like it would be better. Their problem is the drugs. Many of them have family, some of them even have educations. If they could stay sober, they would be capable citizens. Many of them have mental health problems that are either undiagnosed, covered up by their self-medication with illicit drugs, or treatable if the person will actually take the medications. More than one warden has told me stories of model prisoners -so long as they are on their medication -who keep coming back because once out in the world they stop taking their pills.

These are not problems the police or the jailers or the wardens can solve. But they are also different problems. They are also similar problems in that most of them boil down to poor executive function. These people make really bad decisions left to their own devices.

The wardens and the jailers, however, also point out that these problems don’t go away when the person is in prison. Drug addicts with poor executive function don’t make good prisoners. Mental health patients with poor executive function don’t make good prisoners. And since these are most of the people coming into the prisons, they rapidly overwhelm the ability of jails and prisons to deal with them. The local prison has three cells equipped for medically assisted detoxification, and usually more than three prisoners who need it. They have a single nurse on staff and not enough guards to monitor them. Mental cases, until they can be diagnosed, usually end up restrained or in solitary confinement, which does very little for them.

Locking them up achieves nothing, but they also generally haven’t done anything remotely worth executing them for. It is for this reason that the jails, prisons, and judges are extremely interested in anything that could help these people get off drugs or get mental help. With the catch that they have no money to do it.

Helping The Hopeless

The recurring problem is that these prisoners have that low executive function, and we keep finding out that quitting drugs is easy. Most prisoners have done it 5 or 6 times.13 The wardens and jailers would love to have 12 step programs in their facilities, because people trying to get sober are better prisoners, and people who stay sober don’t come back. They don’t have the space or the money.

The court system has implemented drug courts, and ours are wildly successful. If a person completes the drug court program, they are unlikely to reoffend. If. The courts also cream skim the most likely people to succeed, who were also least likely to commit further crimes because, having a criminal record, they’re now useless to the organizations that were using them. (Gangs can identify functional addicts, too.) If you can get one, we have councilors and doctors, and they can help, too, but the refrain remains: we don’t have the space or money.

So the wardens and jailers do what they can: create as much order as possible.14 The hope is that by reducing chaos, they can reduce crime in their charges, and maybe the prisoners will start to learn how to think before they act. Even here, though, the resource constraints show. In order for prisoners to learn to behave, just like children and pets, rules have to be enforced consistently and quickly. We lack the necessary staffing to do so, and so we get randomized draconian punishments that, again, do little for the prisoner’s learning to behave.

Wrapping Up

This e-mail is getting too long, but I hope it’s given some insight into how to think about corrections policy and why the corrections system is interested in rehabilitation entirely aside from recidivism, and the different problems the corrections system faces.

I talked to my member of Congress about it, because I was in DC anyway, and I went to his office. Which is really all you have to do. “A constituent came to our office and said this bill was important to him” will get immediate attention.

As will be a recurring theme, I can’t find the quote, but I believe this is one of Rob K. Henderson’s lines.

And if we’re talking about ideal policies, I’d like almost every squad car to be a two-person unit, but the days of having those kinds of resources are probably past.

I primarily study metropolises, and there’s a neat article in Metropolitan Governance by Elaine Sharp that is mainly about policing sex work, but a subthread in the chapter is that policing has some limited spillover effect. That is, when one jurisdiction cracks down on street walkers, they do hop the border, but they keep going a little ways into the next jurisdiction.

I have related ideas on plea bargaining, but we’re going to pass over them for the moment.

I specify “statutory” because what we colloquially mean by violent and what the law means by violent don’t always coincide. Robbery is the theft of goods from a person with force or the threat of force, and so is usually considered a crime of violence even if you get the world’s most gentle highwayman and he doesn’t even take his gun from his belt.

Talked to a judge once who related the story of a person who was constantly arrested for minor crimes. Person wasn’t particularly dangerous in the judge’s assessment, but he was making a mess for everyone else. He sentenced the man to the maximum sentence he could after all the augmentations for repeat offending -I don’t remember what it all added up to, but it was several years. He then suspended the sentence and told the man that he, the judge, would buy a bus ticket anywhere in the three or four state region. If the man was arrested again in the judge’s territory, he’d apply the entire suspended sentence. Man took the deal.

Though if you care about recidivism, we’re apparently getting better at it. I’ve seen a couple reports from the early 2000s that had recidivism at 70-80% after 5 years, but in 2017 a study had it down to 60-70%.

The one time I’ve been called for jury duty I got placed in the civil trial jury pool, and because I’m a professor of public policy, I got dinged out of both trials I was called to. First time it was a medical malpractice case, and the lawyers agreed they didn’t want me in the jury, and the judge dismissed me. Second time it was an employment suit about a different college than my employer, but as soon as my number was called, the judge looked up and said, “you’re still a professor? Excused.”

To be clear, these are my categorizations of what they describe.

Also, a huge number of them are foreigners working the I-75 route from Sault St. Marie to Miami carrying drugs, pills, sex workers -whatever. An apparently depressingly common statement in interrogation is “this is nothing compared to Venezuela” or some other northern South America country. Also a lot of Russians and East Asians coming in through Canada. Our prisons compare favorably to Vietnam, I’m told.

We do get insane people from time to time. A police sergeant related a story of a crazy naked man trying to burn down a house with a family inside -no connection he was aware of, just a crazy naked man who decided he wanted to burn this house down. When the police arrived to stop him he tried to light the police on fire. Never heard the end of that case, but I presume he was involuntarily committed as he was almost certainly too nuts to assist in his own defense. If he ever did become competent, I’d be happy to try him for the crime, though.

I sometimes get to talk to people who really have turned their life around. They usually credit their 12 step program and their mentors. They also note that it usually wasn’t the first time they tried. Highest number I’ve personally heard was 9 attempts before staying sober for over a year. Lowest number I’ve heard is 3.

I noted at the top that we need to pull data from the analysis with an eye towards the reason the data was created, but this one I actually feel compelled to mention specifically: having spent enough time with wardens and guards, every single one of the rules discussed here is reasonable. The issue is that the prisons are too understaffed to routinely enforce them.

"Locking them up achieves nothing"

Locking them up keeps them from committing crimes against me or my family while incarcerated. We need to deal with the reality of people who are repeat offenders. The judge's "put him on a bus" strategy didn't prevent crimes, just offloaded those crimes to a different jurisdiction.

I’d love to discuss this more in depth with you!